So, what to make of Glenn Gould’s incessant singing and muttering while performing? Some find it intolerable. Others find it charming. Some of us may even have favorite Gould vocalized passages. (One of mine is the 17th measure of the 14th Goldberg Variation from the 1981 recording.) Personally, I find Gould’s singing in no way distracting. I am no longer the big fan of Gould’s pianism that I once was, but that has nothing to do with his eccentric vocalizations. Most of the time, I even forget they’re there. (The subconscious mind must be at work here distinguishing the intentionality of musical tone from the non-intentionality of extraneous sounds.) If anything, Gould’s singing authenticates and humanizes his performances. It reveals a performer so entirely absorbed in the music’s moment and reminds us that this is a performance, even if within the confines of a recording studio. Gould’s mutterings distinguish his recordings from those countless note-perfect recordings available today that take on a fabricated, sterile, and even robotic quality. (Is perfection ever very interesting?)

What I find a bit more off-putting than Gould’s vocal eccentricities are the middle-register hiccups that emanate from Gould’s beloved “CD 318” Steinway piano on a couple of his recordings. The hiccups are perhaps most pronounced on Gould’s 1964 recording of Bach’s Inventions and Sinfonias (the first recording project following his well-known withdrawal from the concert stage) and are apparently the result of Gould’s constant tinkering with CD 318 in order to achieve as harpsichord-like a quality as possible. Gould found the hiccup effect charming enough not to abandon his dear CD318, which traveled with him throughout his concertizing career. (In the early 1970s, CD 318 suffered irreparable damage in a moving accident, which devastated Gould.)

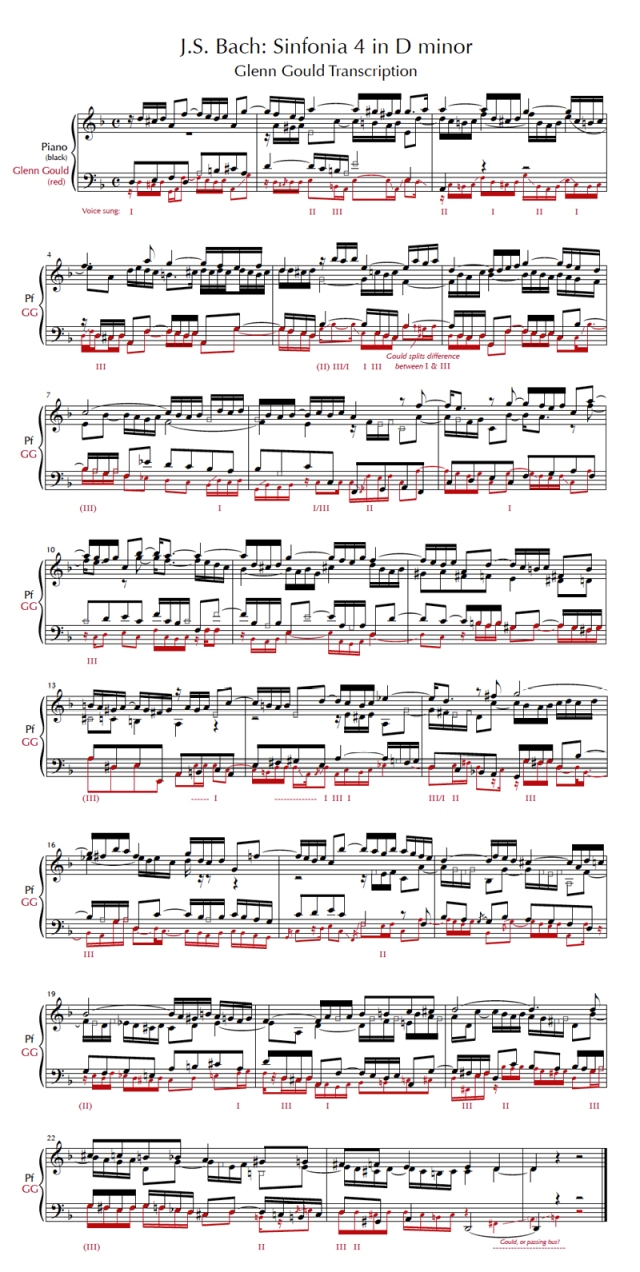

Below is a transcription of Glenn Gould playing and singing the fourth Sinfonia in D minor. The score reflects exactly what Gould played and not necessarily what Bach notated (i.e. embellishments are written out), exactly what Gould sang (notated to the best of my ability), and the hiccups that ring from CD 318 (notated with boxed noteheads). Gould’s notated sung part is obviously an approximation in certain passages given his use of vibrato, frequent portamenti (some before the beat, some after), and occasional intonational imprecision. Whatever you make of Gould’s singing, at least now you can follow along. (By the way, is that Gould himself in the final measures or a passing bus?)

Listen here. (Headphones are an obvious advantage.)

The difficulty of transcribing Gould’s singing depends on several factors such as how fast and loud the piano is, how vocal and loud Gould is, whether the lower piano part falls in Gould’s baritone singing range, etc. (This fourth Sinfonia then is an ideal piece to transcribe as it is a slow work that lies above Gould’s singing range much of the time.) What makes transcribing Gould even possible, however, is that he truly does sing, as opposed to, say, the loud, guttural, untranscribable noises that Keith Jarrett makes while performing. (I am a big Jarrett fan and have learned to ignore all of his noises as well (though jazz improvisation is admittedly a different animal than playing Bach). To me, Jarret’s physical gyrations, which were worse in his younger years, are more distracting than his vocalizations, but perhaps that’s only because I don’t often watch him play.)

Now on to the very important research made possible by this project. Which part does Gould prefer to sing? Outer voices? Inner voice? And how often does Gould provide an added part as has been claimed? Well, Gould sings the top voice 23.1% of the time, the middle voice 24.5% of the time, and the lower voice 51.4% of the time. The fact that the lower voice falls nearest his voice range may be the most logical explanation for this preference. Only 2.2% of the time (for a total of 2 beats in mm. 13 & 14) does Gould sing an added part, and even these moments are more added notes that true parts.

So there you have it.

Another possibility for the bass preference could be that the humming is a subconscious memory device. Most memory issues happen in the left hand, so vocalizing it could help.

If it’s true that most memory issues happen in the left hand, that’s certainly a possibility. Gould did state that his singing was subconscious, a habit he developed early on when taught by his mother to sing while playing. Someone should do further research to see if his preference for singing the lowest parts is consistent.