In a previous post, I examined 46 instances of consecutive fifths and octaves found in the Bach chorales. Here is a summary of what we learned:

- Bach did on relatively rare occasion write consecutive fifths or octaves involving non-chord tones (13 instances). Also, seven chordal consecutives appear in the Bach chorales, all of which involve leaps rather than steps, most of which involve fifths and not octaves, and none of which involve outer voices.

- Consecutive fifths are far less objectionable than consecutive octaves.

- Consecutives involving non-chord tones are less objectionable than chordal consecutives.

- Consecutives in contrary motion are far less objectionable than consecutives in parallel motion.

- Consecutives involving inner voices are far less objectionable than soprano-bass consecutives.

- Parallel fifths created at authentic cadences involved a Re-Do anticipation in the melody over Sol-Fa movement adding the seventh of a V7 are not at all objectionable.

- Bach simply does not write stepwise chordal parallels.

Developing a clearer picture of Bach’s approach to consecutives in the chorales, however, should involve looking not only at the consecutives that he did write, but also the consecutives that he seemingly intentionally prevented. The difficulty of this task lies in the rather obvious fact that we cannot always know the pains taken by Bach to avoid consecutives just from examining Bach’s scores. We have no log of Bach’s thought process through the compositional act. (Robert L. Marshall has done extensive work examining corrections in Bach’s manuscripts, and while his essays on these corrections do suggest that Bach occasionally made corrections in order to fix consecutives, unfortunately Marshall does not expound upon these general statements, nor does he specifically catalogue the manuscripts in which these corrections occur.) Nevertheless, certain musical devices do seem to be regularly employed for what seems to be the explicit purpose of preventing or masking consecutives.

Certain overriding questions are of interest here: First and foremost, does Bach intentionally prevent the kinds of parallels that in other cases he was comfortable writing (as presented in the previous post)? If the answer is no, then our enterprise of developing Bach’s approach to consecutives is further solidified. If the answer is yes, then further questions follow. Are there contextual factors that led Bach to consider certain kinds of consecutives to be allowable in some cases? Does this suggest that Bach’s approach to consecutives developed over time? Does this suggest that the consecutives that he did write were the result of oversight – i.e. “mistakes” – as Malcolm Boyd has suggested? If the answer to this last question is yes, then the question of why such mistakes were made follows.

So what musical devices are employed with any kind of regularity to prevent or mask parallels? Let’s get to it.

Suspensions

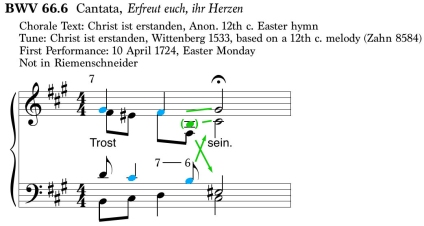

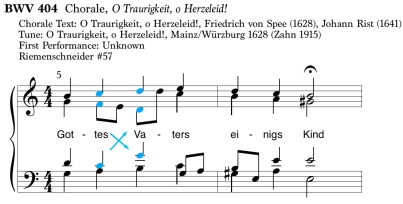

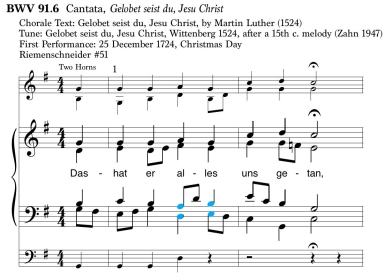

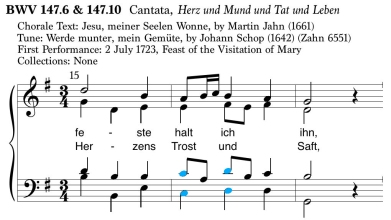

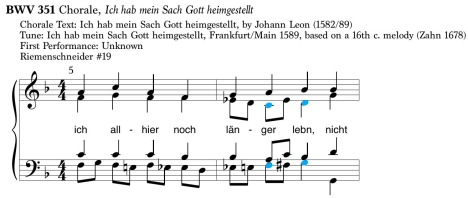

The 7-6 Suspension

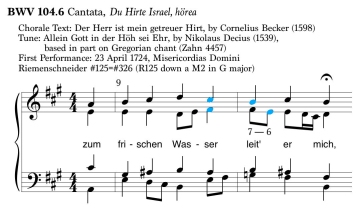

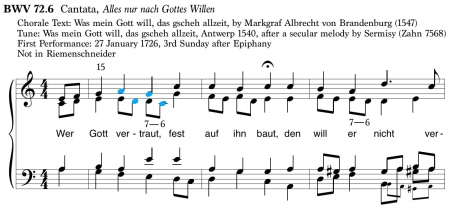

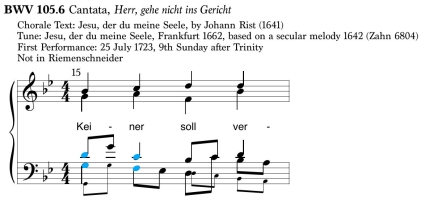

Suspensions are occasionally used to prevent or offset parallels. In particular, the 7-6 suspension frequently masks parallel fifths involving upper voices. In fact, a significant proportion of all 7-6 suspensions do this. Looking at just chorales from the first 100 cantatas (BWVs 1-100), nine of the 38 total 7-6 suspensions (24%) prevent parallels. Remove the suspension and blatant chordal parallel fifths appear. Below are just three examples. Other instances (just from among the first 102 cantatas) include BWVs 7.7 (not in Riemenschneider), m.3/7; 28.6 (R23=R88), m.9; 56.5 (R87), m.21; 66.6 (Not in R), m.7; 78.7 (R297) m.3/7; 84.5 (R112), m.13; and 102.7 (R110), m.8.

EXAMPLE 1

With the exception of BWV 104.6, all of the instances of parallel-masking 7-6 suspensions mentioned here either involve suspension preparations that are off the beat (as in BWV 72.6 below), several involving suspension chains. Only 104.6 above prevents chordal parallels occurring from beat to beat. Does this suggest that Bach did not generally consider 7-6 suspensions to be sufficient in masking beat-to-beat parallel fifths? Possibly. Unfortunately, the incomplete sample size here and the fact that Bach is not averse to using other kinds of figuration to mask beat-to-beat parallels, as we will soon see, make it difficult to arrive at any firm conclusion. If further research confirms that the vast majority of parallel-masking 7-6 suspensions involve off-the-beat preparations, perhaps this suggests that Bach felt more comfortable finding other ways of preventing beat-to-beat parallels.

EXAMPLE 2

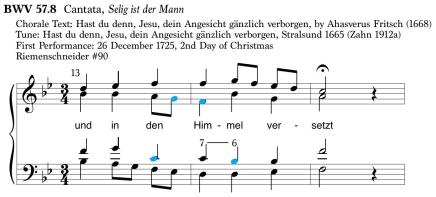

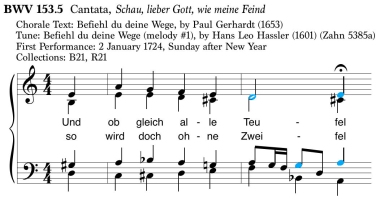

In the first two instances above, as with most cases of these kinds of 7-6 suspensions, the parallel fifths that are masked are chordal parallels, not the kinds of parallels that Bach occasionally allowed in his chorales. Example 3, however, features a 7-6 suspension that masks parallels involving a non-chord tone (passing tone in the alto), parallels that are occasionally found in the chorales. Unfortunately, since it is impossible to know whether Bach added this suspension for the intent purpose of masking the parallels or whether he added it for purely musical reasons, making any assertions regarding Bach’s approach to NCT-involving parallels based on this or similar passages is next to impossible.

EXAMPLE 3

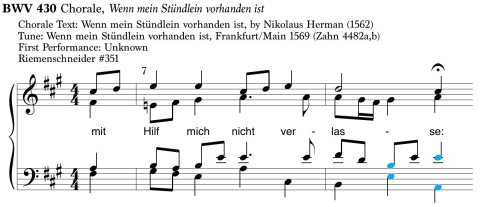

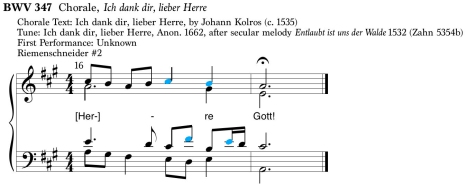

Other Suspensions

Among the four basic suspension types (4-3, 9-8, 7-6 and bass 2-3), it perhaps makes sense that the 7-6 is used most frequently in masking parallels since the 7-6 suspension almost always involves a delayed chord root, and parallel fifths almost always involve the movement of root and fifth of one chord to root and fifth of another. Both the 4-3 and the bass 2-3 suspensions generally involve a delayed chord third, a chord member rarely involved in objectionable parallel motion. So these two suspensions cannot generally be used to mask parallels. As for the 9-8 suspension, Bach does not use the 9-8 to mask parallel octaves.

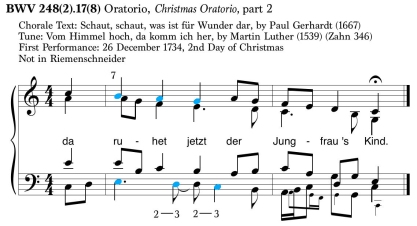

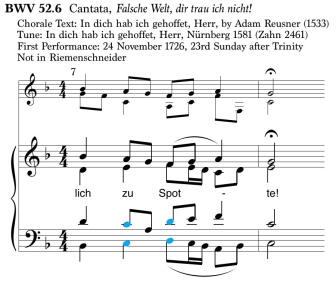

Below, however, is a rare instance of the use of the bass 2-3 suspension preventing parallels, and it actually features two! (The sequential force of the suspension chain actually helps in attenuating the effect of the staggered parallels.)

EXAMPLE 4

To summarize, Bach does indeed use suspensions to mask parallels. In the vast majority of cases, the suspensions are prepared off the beat further attenuating any negative effect of the staggered fifths. While it seems obvious that in these cases Bach has intentionally inserted suspensions to prevent chordal parallels given the frequency with which such suspensions appear, in the one case (BWV 72.6) of non-chordal parallels involving NCTs, parallels that Bach occasionally allows, it is impossible to know whether the 7-6 suspension was added for the intent purpose of masking the parallels or whether it was added for musical reasons.

Voice-Crossing

Naturally, consecutive perfect fifths and octaves are considered objectionable only if they involve the same two voices. A perfect fifth between soprano and alto in one chord followed by a perfect fifth between soprano and tenor in the next is not considered objectionable in any way. Bach frequently uses this principle in conjunction with voice-crossing to prevent objectionable parallels. This seems like a feeble way of getting around a potentially inevitable instance of parallels, a kind of cheat. Yet, Bach resorts to this technique regularly! In the passage below, another instance of a 7-6 suspension masking parallel fifths is immediately followed by a set of non-objectionable parallel fifths involving three voices. The natural resolution of the tenor’s B3 would most logically be the C#4. Since this would create objectionable parallels with the soprano, Bach simply gives it to the alto and has the tenor melodically descend a diminished fifth to E#3, the most logical resolution of the alto’s F#3. The alto’s octave descent crossing the tenor perhaps helps to delineate the two inner voices, while at the same time attenuating any negative effects of the disjunct melodic leaps.

EXAMPLE 5

In all honesty, this resembles the kind of clumsy work-around often encountered in beginning part-writing exercises of first-year theory students (at least the observant ones who detect the problematic parallels!). Yet, Bach apparently considered such methods legitimate. And, of course, Bach never fails to create strong, even beautiful, melodies in such contexts.

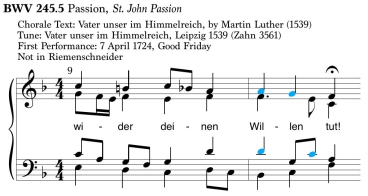

Example 6A demonstrates the voice-leading challenges that often accompany the Phrygian half cadence. The most logical place for the needed B-natural is in the tenor. Yet, what is the alto to do? Moving to B-natural is doubly problematic (for both melodic and chord doubling reasons) and moving to G4 produces parallel fifths with the soprano. The only solution is D4, thereby doubling the chord fifth, a solution not entirely objectionable, though perhaps not as desirable as a doubled root (G).

EXAMPLE 6A

However, instead this doubled-fifth solution, Bach achieves a doubled-root V chord through the use of voice-crossing (Example 6B). On beat 1, tenor and alto simply switch notes in preparation for switching back at the moment of cadence. The objectionable parallels imagined in Example 6A are still there, only three voices are involved, thereby legitimizing the voice-leading.

EXAMPLE 6B

Here is another problematic scenario:

EXAMPLE 7A

In Example 7A, a half cadence to a close-structure V chord is achieved. However, the chorale melody (which Bach is not at liberty to simply change) causes issues moving forward. If the V-vi progression that begins the next phrase is desired, what are the alto and tenor voices to do that don’t cause objectionable parallels with the bass? Take a moment to imagine a solution before seeing Bach’s version in Example 7B below.

EXAMPLE 7B

Bach breaks one of the fundamental “rules” of first year part-writing. He writes voice-crossing involving an outer voice! One might argue that the aural effect of the passage essentially does change the chorale melody, and that the pseudo parallel octaves involving both alto and soprano with the bass does not sufficiently attenuate its negative effect. Apparently, Bach felt otherwise.

Here’s a third passage that needs fixing. Blatant parallel octaves and fifths appear in the ascending voice leading of this IV-V progression (in C major). Were the bass in the lower octave providing more space for the tenor, alternative solutions are more easily imaginable. But leaving the bass where it lies, what solutions are possible?

EXAMPLE 8A

Bach’s solution is rather brilliant (Example 8B). The swapping of inner voices here in no way changes the chord structure of the problematic passage above. The precise notes of these two chords are identical in both passages! The inserted passing tone in the alto (E) draws attention to the voice-crossing, further attenuating any negative effect of the pseudo parallels. The alto’s octave leap that follows is combined with the tenor’s octave leap of its own, though in the opposite direction. The final result is a passage featuring two wonderfully striking inner voice melodies, a feature so common in Bach’s chorales.

EXAMPLE 8B

In each of the cases cited here, voice-crossing prevents choral parallels rather than the kinds of parallels involving NCTs that Bach occasionally allowed. This seems to true for all other instances of voice-crossing preventing parallels that I have found. A couple other such passages are BWV 67.4 (not in Riemenschneider), m.2; 86.6 (R4), m.13; 330 (R33), m.2.

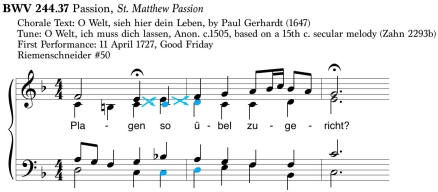

Chordal Leaps

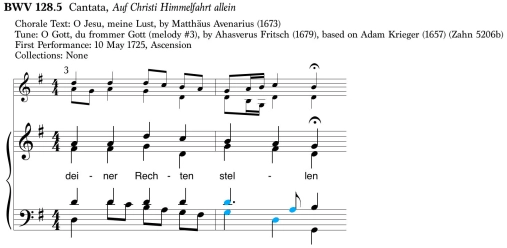

Does Bach use chordal leaps to prevent parallels? Yes, he does, and frequently. Perhaps the most common type of parallel-preventing chordal leap is the anticipation figure that staggers the consecutives, as in Example 9. Notice that the anticipation figure, E4 in this case, is a chord tone within the first chord (E major). It is an anticipation figure, not a true non-chord tone anticipation. And here, a point is worth stressing. With the exception of suspensions, Bach does not typically use surface non-chord tones to prevent chordal parallels. A simple passing tone, anticipation, or incomplete neighbor does not sufficiently mask objectionable consecutives fifths or octaves. Chordal figuration, on the other hand, is used by Bach to prevent parallels, in most cases staggering them.

EXAMPLE 9

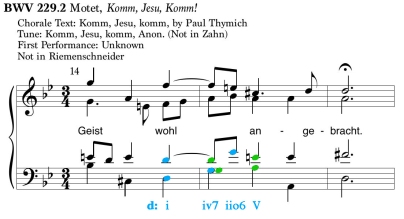

This kind of chordal leap anticipation figure can be found in numerous chorales. Here are just a few other examples: BWV 70.7 (not in Riemenschneider) m.28; 95.7 (not in Riem.), m.12; 99.6 (not in Riem.), m.2; 144.3 (R3), m.2; 229.2 (not in Riem.), m.7; 244.54 (R74), m.15.

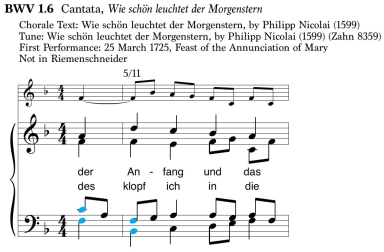

In the previous examples, consecutive fifths are staggered by the early arrival of one of the voices. In the next example, parallel fifths are staggered by the delayed arrival of one of the voices.

EXAMPLE 10

Once again, notice that the tenor’s D4 which carries over into beat 2, is a chord tone in the beat 2 chord. Thus, no non-chord tones are involved here.

Chordal leaps other than the simple staggering of parallels feature in Examples 11 through 16 below. The first four mask parallel fifths while the last two mask parallel octaves. In all cases, these chordal leaps prevent chordal parallels.

EXAMPLE 11

EXAMPLE 12

EXAMPLE 13

EXAMPLE 14

EXAMPLE 15

EXAMPLE 16

While the previous chordal leaps occur off the beat staggering beat-to-beat parallels, Bach also occasionally interrupts parallels by inserting a different chord member on the beat. The following two examples break up parallels (fifths in both cases) with on-the-beat chordal leaps.

EXAMPLE 17

EXAMPLE 18

A few other examples of chordal skips masking consecutives are BWV 20.7=20.11 (R26), m.1; 22.5 (not in Riem.), m.6/15; 41.6 (R11), m. 44; 124.6 (not in Riem.), m.13; 281 (R6), m.5; 334 (R73), m.10.

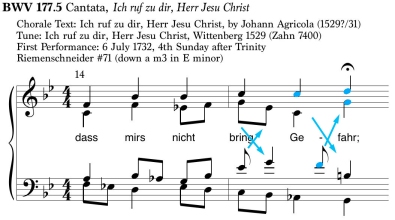

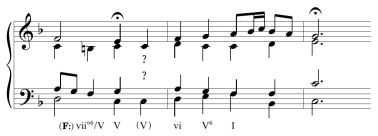

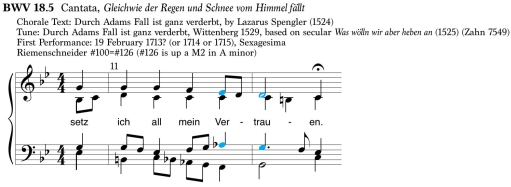

Anticipation Figure Creating a New Chord

Earlier, I stated that Bach does not typically use basic surface non-chord-tone figuration such as passing tones or anticipations to mask parallels. However, Bach does not object to using anticipation figures (not true NCT anticipations) that create new chords to break up parallels. Perhaps the most common situation in which this occurs is the ever-challenging iv7-V progression with its potential parallel fifths – chord third and seventh of the iv7 moving to root and fifth of the V. As in Example 19, the parallel fifths are staggered by resolving the seventh early, thereby transforming the iv7 into a iiø65 chord. Two other instances of this particular anticipation figure are BWVs 162.6 (not in Riem.), m.10; 177.5 (R71), m.11.

EXAMPLE 19

Other Methods

Two additional examples of Bach using surface devices to prevent parallels are given below. These instances are individual, not representing a broad category, but they demonstrate other creative ways in which Bach prevented parallels.

In one sense, Example 20 features a leap like the many other chordal skip examples already seen. The difference here is that the leap is to a chord tone of a new chord. The F chord, V of Bb, that appears on the beat of beat 2 moves deceptively to a moves to a vi chord (G minor) on beat 3. The chordal parallels that occur from beat to beat are broken up with the interpolation of a viio7/vi between the two chords. The chromatic ascent of the bass further removes any negative effect of the beat-to-beat parallels.

EXAMPLE 20

Example 21 comes from Bach’s motet, Komm, Jesu, Komm!

EXAMPLE 21

This curious passage features two instances of parallels that are, in a way, staggered by each other. Remove the tenor’s D on beat 1, and parallel octaves occur. Remove the G, and parallel fifths occur. But the curiousness of the passage doesn’t end there. Is the soprano’s F-E motion a suspension? If treated so, then the harmony is not iv7, but iiø65. Yet this interpretation would suggest that the tenor’s D is the chord seventh, which should by “rule” resolve down by step, a resolution that would problematically double the soprano’s C# leading tone on beat 2. The alto’s accented passing tone (A) perhaps contributes to the harmonic ambiguity of the moment, further attenuating any sensed pull of the tenor’s D to C#. The manner in which Bach has avoided all potential problems here is ingenious. (Side note: This “chorale” is, in fact, not a true Lutheran chorale. Its melody is (presumably) composed by Bach, so one might suggest that Bach could have changed it here to allow for the tenor’s movement to C#. Given Bach’s general approach of composing outer voices first, perhaps Bach did not want to disturb that outer framework after the fact.)

Conclusion

To summarize our findings here, Bach uses certain musical surface devices to mask or prevent parallels. These devices include 7-6 suspensions, voice-crossings, chordal leaps, and anticipation figures into new chords. He does not, however, use 9-8 suspensions or other surface non-chord tones like retardations, anticipations, incomplete neighbors (escape tones or appoggiaturas), or passing tones (accented or unaccented) to prevent parallels.

What does this information contribute to our overall understanding of Bach’s approach to consecutive perfect intervals? Considering that, by and large, the kinds of chordal parallels that are prevented in these examples are chordal consecutives, are consecutives in parallel motion rather than in contrary motion, and thus, are not the kinds of parallels Bach occasionally allowed in his chorales, the data here largely coincides with the findings from the previous post regarding the consecutives Bach did write. There is no evidence from this research, then, that the NCT-involving consecutives occasionally found in Bach’s chorales are “mistakes,” (as Malcolm Boyd has suggested).

For those of us who teach part-writing, might all this data change the way we approach the “rules” regarding parallel or consecutive perfect intervals? Instead of discouraging students who attempt creative (or not-so-creative) solutions to problematic voice-leading, perhaps we should encourage them to do so! After all, if Bach is our supreme model for part-writing (as he should be), shouldn’t we also model our ways of cheating after him as well?

And for you students who are currently studying part-writing, the next time your professor marks your parallel-masking suspension or voice-crossing as wrong, feel free to show him or her any one of the Bach examples presented here. Only don’t tell them where you found them!

Fascinating findings! As always, terrific information, clearly explained. A true delight!

Thanks, Keith! Always great to get your feedback. Hope you are well.

Thanks for this post. I’m brushing up my theory, and wanted to study Bach chorales. Which would you suggest as a starting exercise?

Thanks for reading and for the comment! Your question is a good one but a difficult one to answer without knowing your intentions for studying and without knowing your background (i.e. what theory you’ve had). But at any rate, playing through the chorales and analyzing them is always beneficial, generally speaking. The Bach chorales are truly little gems of musical part-writing. If you have experience with Roman numeral analysis and have a copy of the chorales, you could also work through a few chorales and check them against analyses provided here: http://www.lukedahn.net/Scores/Chorales1to18.pdf

I am revising book 1 by lovelock, so that I can teach ideas from there, played on the piano, where I find them in my students Piano pieces. Thanks for the link!

First off, great work. But I gotta tell you, examples 17 and 18 are unfounded. The real issue with example 17 is parallel octaves on beats 3 and 4 between the Soprano and Tenor voices. For example 18, there is no flaw in the counterpoint you highlighted. You cannot say that a P5 is in any way parallel to an interval NOT on the next immediate beat. Divisions of the given beat level are not considered in traditional baroque counterpoint. The rest of the work you’ve done here is great. Thanks for the post!

Thanks for the comment. You are right that the staggered octaves in Example 17 are more problematic than the staggered fifths. However, there is nothing in this post suggesting that these instances of staggered parallels are problematic. Your comment about the divisions of the beat is quite curious. I’ll respond to this in your other posted comment.